Whence the "Public" in "Public Health?"

I’ll start this post with the punchline. The word “public” is being used to imply that government intervention is necessary without actually making that argument. There is no philosophical or technical grounding behind the word “public” in “public health”. It just means, “all the health-related stuff that governments typically do or want to do.” I want to call this out and insist on an explicit argument whenever someone suggests government intervention, particularly with regard to our health. I’ll also insist on observing the distinction between public and private. We shouldn’t let people get away with claiming something is the former when it’s clearly the latter. If anyone reading this thinks I’m being a language pedant, you’re missing the point. Calling something “public” has implications for whether the government should be involved, so it’s important that we not simply let the word be thrown around without interrogating the implications.

In economics, there is the concept of a “public good.” The word public is actually doing some lifting, it’s not just a filler word. It has a technical definition, which contrasts it with the antonym private. A public good has two properties. It’s something that is non-rivalrous, meaning my use of the good doesn’t impede someone else’s use of it. (Such as the protection of nuclear deterrence or the enjoyment of a municipal fireworks show.) It’s also non-excludable, meaning the producer can’t prevent someone from enjoying the benefits of the good. Supposing it’s trivially easy to steal copies of software or music, these goods become non-excludable because their makers can’t exclude users. They thus have no means of forcing customers to pay up, and so no reason to produce those goods in the first place. Obviously these particular problems of excludability have been solved, since music and software are sold in the marketplace. But supposing there is a reasonable claim that something desirable is a public good, that might be a legitimate reason for government to supply or subsidize it. Governments have the power to tax, thus avoiding the non-excludability problem. Governments can effectively force the “consumers” of said public goods to pay up. And once the good is produced, it can be consumed by all citizens since my consumption doesn’t diminish your consumption.

Sometimes people wrongly claim that something is a public good, but it’s easy to check these claims and determine if someone is trying to rhetorically sneak something past us. Public schooling is not a public good. It is excludable and rivalrous. The school can exclude students from attending, for example by expelling children who misbehave or denying attendance based on the child’s address. Occupation of a desk by a student means another student can’t occupy that same desk, so clearly it isn’t non-rivalrous. (By contrast, if the government were to broadcast video lectures over the airways, that could be non-rivalrous and non-excludable.) The benefits of schooling accrue primarily to the student, not to third parties. No, when someone claims schooling is a public good, they are trying to sneak in the assumption that government must provide it without giving a good reason.

As an academic discipline, economics has its shit together. This is in sharp contrast to “public health.” The “public” here has no formal meaning that distinguishes it from “private”. It’s a stand-in for “encompassing various tasks that governments tend to do.” I’m trying to imagine an economist aggregating up many examples of private goods, then claiming that the resulting aggregation is an example of a public good. Consumer widgets are private goods. Summing up widget purchases across a population does not generate a public good. But try the same exercise with smoking or obesity. The decision of a person to smoke or otherwise live an unhealthy lifestyle is clearly a private health decision. Your smoking or obesity mainly harms you. But public health bureaucracies routinely claim jurisdiction here. They will aggregate these private decisions across a large population and claim that the resulting aggregate is transmogrified into “public health.” They have an agenda, and they sneak it in with clever word choice. They would prefer that you make a different decision, so they throw around the word public when referring to private choices.

There is a giant fallacy at work here. Multiplying a (perhaps regrettable) private health decision a hundred million times doesn’t convert the “private” to “public.” Public health bureaucrats concern themselves with these kinds of aggregate statistics. “We counted the number of smokers and the resulting years of life lost due to this nasty habit. Look how big and scary this number is.” Or perhaps it’s, “Look at how this number compares to other nations. Shouldn’t we all be so embarrassed?” It gives the impression that public health is really about reshaping private decisions so society presents an attractive tableau. (Presents it to whom? To rival nations? To the government statisticians who obsess over such things? To demagogue politicians who use these stats to whip up a moral panic? It’s not clear for whom this tableau is being crafted, but someone is presumably supposed to care that this problem is being measured and corrected. Otherwise why would they bother?)

That is a shame, because there genuinely are matters of public health in contrast to private health, with the distinction perfectly mirroring the private/public distinction in economics. Arresting the spread of a potential epidemic is real public health. I am glad someone was actively contract tracing and isolating cases of Ebola during the 2014 outbreak. It’s probably also valuable to have a government entity tracking the emergence and spread of the flu season. This might be actionable information for some citizens, e.g. for elderly or otherwise vulnerable individuals who wish to stay home when flu prevalence is high. Perhaps they choose to do their grocery shopping early in the morning when most people are still sleeping, or maybe they decide to isolate at home rather than going to social events.

Disseminating accurate information about the health effects of various diets or substance use might also qualify as public health. Assuming everyone is fully informed, their diet and substance use decisions are strictly private matters. But basic research and accurate data are arguably public goods. It may be costly to conduct a randomized controlled trial on a particular diet or to aggregate scarce data to determine the long-term effects of smoking on lung disease. It might not be obvious that some fad diet is unhealthy (or perhaps healthy after all, contra the accepted wisdom). We might all suspect that cigarette smoking has bad health effects, but sharply quantifying this would be difficult without some central authority dumping tons of funding into the research. I’ll grant that it’s legitimate for public health agencies to try to correct genuinely mistaken impressions by the public, supposing that their ignorance is leading to them making poor decisions. But there are important caveats here. For one thing, public health should not have an agenda of directing people to the “correct lifestyle.” They should not have an opinion on whether or not you should smoke. Their task is to accurately articulate the trade-offs with regard to smoking, not to put their thumb on the scale and compel you to quit or to never start. In reality, public health institutions often have an agenda in mind, such as “reduce smoking and obesity”, then they marshal The Science (TM) in service of that agenda. They need to be reminded, and reminded often, that it’s not their place to do so. Another caveat is that public health officials need to be transparent about uncertainty when it comes to the information they’re providing. Suppose they tell us that smoking a pack a day removes seven years from your life, but this is based on comparing “pack a day” smokers as a population with non-smokers (so a univariate analysis, not adjusting for confounders). A more rigorous study might contemplate that smokers are different from non-smokers for reasons other than smoking itself, and such a study tries to adjust for confounders. The more sophisticated study might find that smoking only reduces your life expectancy by, say, four years. (These numbers are made up, but I think that seven years of lost life due to smoking is a common estimate.) Public health officials are tempted to reach for the higher numbers, because they serve the goal of getting people to quit smoking. But it’s their duty to report the lower figures and explain that these are more plausible estimates of the cost of smoking. They ought to show humility when there is scientific dispute over various health recommendations. If public health officials are first deciding what they want you to do and then marshaling “evidence” in favor of that end goal, they are committing malpractice.

In economics, you generally have to demonstrate some kind of market failure or externality to justify government intervention. The discussion of public goods above is an example: free markets will tend to underproduce public goods, so it might be desirable for the government to step in and produce them. Pollution is another such example. If polluters don’t have to pay the social cost of polluting the air and water, they will tend to over-produce pollution (compared to whatever the socially optimal level of pollution might be). Under this logic, the government has no business subsidizing, banning, or discouraging common consumer goods, where the full costs of production are borne by the producer, and the costs and benefits of owning them are felt by the consumer. One has to demonstrate that some third party (someone not party to the transaction) is injured to justify government intervention. You can’t simply say, “I wish people wouldn’t watch such shitty TV programs. Don’t they know there’s a higher class of entertainment?” A social reformer might try throwing around the word “public” in order to impose his preferences on the rest of us. Such a person might refer to trashy broadcasts over the public airwaves or degradations of the public discourse by low-brow cultural products. But I hope we can agree that it’s not legitimate for government bureaucracies to define the good life for us, then try to impose that on us against our wishes.

I imagine a 2x2 matrix of public health categories. One axis is “Can you impose harm on others?” Communicable diseases. Drunken or distracted driving leading to auto accidents. Air pollution. Obesity does not qualify, because your obesity primarily harms you. Anything with health implications can be rated along this dimension. Another axis is “Can you, at reasonable cost, avoid injury?” Basically, are you opting in to being harmed, or is it unreasonable to expect you do avoid situations in which harm arises? Second-hand smoke may be an externality if you truly can’t avoid it. But anyone who goes to a smoky bar is opting in. On the other hand, it’s unreasonable to tell people “If you don’t like drunk drivers, avoid the roads!” Public health should have no jurisdiction when there is no external harm or when there is such harm but third parties can costlessly avoid it or can be thought of as opting into it.

It’s reasonable for a public health bureaucracy to concern itself with pollutants. Measuring pollution levels, conducting clever studies to measure the health effects of pollution, etc. It’s also reasonable for them to publicize things like drunken driving. If the public is generally ignorant of the level of risk, an information campaign makes sense. It could be the case that both the drunk drivers and the potential victims are underestimating the risk. If the public is aware of the risk but feels powerless to stop drunk driving, it might be appropriate for a public health bureaucracy to engage in some kind of policy advocacy. What’s not legitimate is for the public health bureaucracy to simply decide it doesn’t like some emerging trend of “unhealthy” behavior and then attempt to reshape the world to its liking.

Epidemic disease is certainly the purview of public health. Really it’s the classic public health problem. Accurate information is a true public good (for example, about the epidemic’s geographic spread and severity of illness). The spreading of a disease is a kind of externality. It’s an interesting phenomenon, because it’s more reciprocal than the cases of pollution or reckless driving in the sense that there isn’t a clear aggressor or victim. Can I insist that you stay home, because your venturing out into public makes it more likely that I will get sick? Or do you get to insist the same of me? And if the answer to both is “yes”, then for whom exactly are we preserving the common space? In the case of widespread communicable diseases, it’s unfair to tell people that they could simply avoid the illness if they wished to. Your only option for doing so might be “become a total shut-in.” (And that may not even work if the virus is spreading through the building’s HVAC system, a trick that Covid allegedly learned.) But it’s also unfair to accuse you of generating “external costs”. It’s not clear where the duty to protect yourself stops and the duty to protect others begins. (Paging Ronald Coase, who pointed out that externalities and policies that address them often have reciprocal costs. Externality-producing behavior X harms you, but banning it harms me.) This is a classic public health problem, but not because there is a clear perpetrator and victim.

The case is more clear-cut for diseases that don’t spread easily enough to become a full-on epidemic. In the case of Ebola or various STDs, we can think of the infected person as having a duty to not spread the virus, to isolate once they’ve been identified as a potential spreader. Any kind of communicable disease can be modeled by the tools of epidemiology. We can think of this as a classic exercise in public health, though the experience of Covid modeling should give us pause. The early Covid models were famously inaccurate, overstating death rates and completely missing the timing of the epidemic’s spread. Still, we can use such models to get intuitions about “How many people have to be infected/vaccinated to reach herd immunity?” and “How thoroughly do we have to isolate to arrest the spread of the disease?”

Drugs of abuse are an interesting case. I’ve already mentioned cigarette use and drunk driving, but there are also the illegal drugs. There are certainly cases of “externalities”, people who become so intoxicated that they destroy property, wander into traffic, or perhaps assault a random stranger. Again, I would insist on a clear distinction between self-harm and harm imposed on third parties. The former is private health and is none of the government’s business. The latter is legitimate for public health to concern itself with, so long as it recognizes the distinction. Some simplistic analyses of drug policy treat every user as a potential junkie, as if human beings had no agency. It’s a mere random casting of the dice that determines whether a person turns into an anti-social junkie or keeps their drug use under control and remains a productive member of society (as the vast majority of drug users do). I think it’s probably fine for public health institutions to track general rates of use of these substances, provided they don’t become an advocacy group for particular policies. I would argue, have argued, that our public health institutions failed us by helping to craft (and failing to correct) a false narrative of the opioid epidemic.*

Government crack-downs on drug use have often been counter-productive from a public health standpoint. Crack downs on the availability of prescription opioids led to an explosion of heroin deaths, followed by the widespread use of fentanyl, which is even more potent than heroin and therefore harder to dose accurately. It’s unfortunate that public health bureaucracies and political institutions have a tendency to “optimize in one dimension”, often failing to foresee the (often obvious) adjustments people will make to their policies. Reducing the availability of relatively safe prescription opioids (with transparent, predictable dosing) leads drug users to reach for illicit heroin and fentanyl, which dramatically raises the risk of overdosing. Making it harder to get a prescription for Ritalin (because it’s a potential “drug of abuse”) leads drug users to seek out methamphetamine. Setting up roadblocks to nicotine vaping causes smokers to continue using cigarettes. “Drug paraphernalia” laws made it difficult to acquire clean needles, leading IV drug users to share used needles and starting an HIV epidemic in that community. Governments will often push on anything that moves to demonstrate that they’re doing something about a problem, but they fail to take responsibility for the predictable consequences. A holistic approach to these problems often leads to the conclusion that doing nothing at all is literally the best course of action. Staying one’s hand requires self-discipline, and admitting you lack a solution requires humility. Our political institutions lack these traits. Public health people can’t help but fall into “do something”-ism, the notion that some action must be taken against a problem even when all options are counterproductive.

It’s worth pausing here to draw the distinction between what an omni-competent government could do versus what our real-world government is likely to do in practice. We wage the war on drugs and epidemics with the government bureaucracy we have, not the bureaucracy we wish we had. Our technocrats are not all-wise. They fall for the same trendy nonsense as the general public. The voting public, which in theory disciplines the government to behave itself, is terrifyingly ignorant and often (usually?) asks for the wrong policies. Politicians are demagogues who tell the voting public what it wants to hear rather than what it needs to hear. They sometimes overrule the public in favor of advice by good technocrats, but again these technocrats are prone to making basic mistakes.

I should dispose of some arguments that are commonly used in the public health space. I find it blindingly obvious that the person who wants to ban smoking is really a paternalist. They think smokers are behaving foolishly and want them to make a different decision. But nobody cops to being a paternalist. They often justify government intervention by appealing to third-party costs. A common one is to point out that expenditures for healthcare often come from the government. Unhealthy lifestyles lead to chronic health conditions, and the person who harms himself is often benefitting from some government program like Medicare or Medicaid or a long-term disability program. Thus we’re all paying for this person’s bad decisions. To this, let’s point out that these people with unhealthy lifestyles also tend to die early and thus save the government several years or decades of expensive healthcare spending and Social Security payments. I don’t know how this nets out, it might be the case that smoking merely brings those expensive years of healthcare spending forward in time rather than cutting them off. But let’s ask if the people who make this argument are actually committed to it. That is, if a thorough analysis finds that obesity and smoking actually save the taxpayers money, are they going to flip and say we should subsidize and encourage these lifestyle choices? If the answer is “No”, then these aren’t serious people. Intellectual honesty compels us to follow an argument where it leads. These people are simply throwing out any plausible-sounding argument in the hopes that some of them will stick. There is basically zero chance that any of them would flip the conclusion if the analysis came out in the other direction, so we should dismiss this argument. (I’d ask a number of other awkward questions here as well. Are you willing to cut people off from the government spigot if they engage in unhealthy behaviors? If that’s the real concern, why not? Are you un-PC enough to call for a tax on obesity? Why not, if the concern is that unhealthy lifestyle choices cost the government money?)

Another kind of argument is that people tend to be ignorant about good health information. They might underestimate the health effects of smoking, or they may not realize that their multiple sodas consumed per day is causing their obesity. This is partly an empirical question: “How well do people’s impressions of the health effects of smoking or snacking correlate with the truth?” Jacob Sullum’s book For Your Own Good presents compelling survey-based data showing that smokers and non-smokers alike tend to overestimate the health impacts of smoking. Should we then encourage people to smoke, since their ignorance is presumably causing them to smoke less than the optimum amount? If “No,” then this is just another throw-away argument that public health officials don’t actually believe and won’t follow to it’s actual conclusions. Another obvious point here is that the government tends to be a major purveyor of health misinformation. How do we quantify the health impacts of nudging people toward low-fat diets (necessarily higher in carbs), or low sodium diets that likely had no health benefits?

There was plenty of misinformation in the Covid era as well. The most famous example is the early admonishments against buying face masks. (Because they’re not effective, and by the way medical professionals need them so don’t go buying them up and creating a shortage. Many commentators pointed out the contradiction at the time.) They then changed course and totally oversold the effectiveness of masks. (They were right the first time, masks were basically worthless in arresting the spread of Covid.) Whatever you think of the risks and benefits of the mRNA vaccines, it’s pretty clear that a slight mutation allowed the virus to rip through a thoroughly vaccinated population. Officials were totally dismissive of the age gradient in the severity of the disease, as if this had no policy implications. It emphatically did. Young people under about 40 had basically nothing to worry about, and school-age children were nearly immune. This had obvious implications for whether or not to close schools, who should be isolating at home, who should vaccinate, and a number of other things. You wouldn’t have known this if you’d gotten all of your information from the CDC.

I’m actually willing to retreat slightly from a strict libertarian position here and accept that a society that really dislikes cigarette use is going to try to discourage it. Same for drug use, obesity, etc. Official finger-wagging, taxing, and banning of “undesirable” activities is to some degree inevitable. Fine, but let’s be honest enough to call it what it is. It’s not public health. It’s more like “We don’t like your private health decisions, so we’re going to select something else for you.”

___________________________________

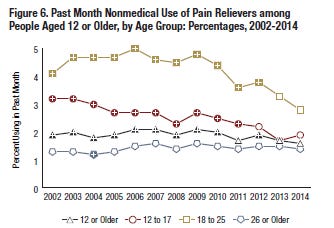

*If you’re not familiar with my past writings, I’ve made a big stink about the chart below, published in a government report on rates of drug abuse. It obviously contradicts the story that loose opioid prescribing kicked off the opioid epidemic by creating a new class of opioid users. Rates of abuse are flat, and so is a similar line that tracks “opioid use disorders” (see the above link for details). So a very important piece of the causal chain is broken in the standard story about the opioid epidemic. This sad episode represents a failure of the public health establishment to calm a moral panic with accurate information.

In case anyone wants to pick a fight over the “technical” definition of public health, it really does look as though it’s defined to mean “whatever the government is doing or would like to do with respect to health policy.” There really isn’t an objective definition that would differentiate it from private health, something that’s none of the government’s business.

Here is what I get when I google “define public health”:

Here’s ChatGPT’s response to the prompt “define public health”. Note the words “and individuals” in the first and second sentences. And under bullet 2, some of the items listed, such as healthy eating and tobacco cessation, are clearly private health matters:

“

Public health refers to the science and practice of promoting and protecting the health and well-being of communities, populations, and individuals. It encompasses efforts aimed at preventing disease, prolonging life, and improving the quality of life through organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private communities, and individuals.

Public health is concerned with the overall health of populations rather than focusing on individual health outcomes. It involves assessing and monitoring the health status of communities, identifying health challenges and risks, and implementing interventions to promote health, prevent diseases, and address health disparities.

Key areas of public health include:

Disease Prevention and Control: Public health works to prevent the occurrence and spread of diseases through measures such as immunization campaigns, health education, and surveillance systems.

Health Promotion: Public health promotes healthy behaviors and lifestyles through education, awareness campaigns, and policies that encourage physical activity, healthy eating, tobacco cessation, and substance abuse prevention.

Environmental Health: Public health addresses the impact of the environment on human health, including monitoring and regulating air and water quality, ensuring food safety, and managing waste disposal.

Epidemiology and Biostatistics: Public health utilizes data collection and analysis to identify patterns and trends in disease occurrence, risk factors, and health outcomes, enabling evidence-based decision-making and policy development.

Health Policy and Management: Public health professionals develop and implement policies and strategies to improve healthcare systems, ensure access to healthcare services, and manage public health programs effectively.

Social Determinants of Health: Public health recognizes that health is influenced by social, economic, and environmental factors, such as income, education, housing, and social support systems. Addressing these determinants is crucial for reducing health disparities and promoting health equity.

Public health is a collaborative effort involving government agencies, healthcare providers, community organizations, researchers, and individuals working together to safeguard and improve the health of populations.

“

I have a public health textbook within arms reach of where I’m sitting, and it takes a similar approach to defining public health. So I don’t think I’m cherry picking.